You're constantly posing questions that you try to answer. The action between the question and the solution is what I think is the creative act. The fumbling around and trying things, and making a line and erasing it, going back and drawing the line, and saying "That's better." You've made some kind of progress in answering that question. It tends to lead to something else, but you're building all the time, you're always looking for those answers. I think that’s essentially what art is.

— Rudy Autio

Over the course of a career spanning more than fifty years, Rudy Autio emerged as one of America’s preeminent ceramic artists. No sampling of iconic artworks made with clay after 1945 would be complete without one of his “ladies and horses” pots. The work for which he's best know was ground-breaking, and he, along with a handful of other innovators, blazed the trail for contemporary ceramics in America and beyond. Yet Autio wasn't merely a disrupter, forging something new through blunt rejection of traditions and norms. There's a timeless quality to his work. It looks back at the same time that it looks forward. It is forthright in its allure, accessible, even plain-spoken. Now, 13 years after Autio's passing, and nearly 70 years since he made his first marks on the art world, his work remains compelling, multitudinous, beautiful.

Autio also had tremendous influence as a teacher and mentor. He shepherded the Archie Bray Foundation for the Ceramic Arts through its earliest years. In 1957 he established the ceramics department at the University of Montana, where he taught continuously until 1985. He conducted more than 100 workshops around the country and internationally. His students—some of whom have gone on to have very successful, very influential careers of their own—remember his generous spirit and soft-spoken encouragement. He instilled in them the notion that art-making was the marriage of craft and feeling, an interplay between emotional honesty and material problem-solving. To this day Autio's legacy is palpable in the scope and substance of American ceramic arts.

Formative Years

Aviation Machinist Mate 3rd Class, c.1945

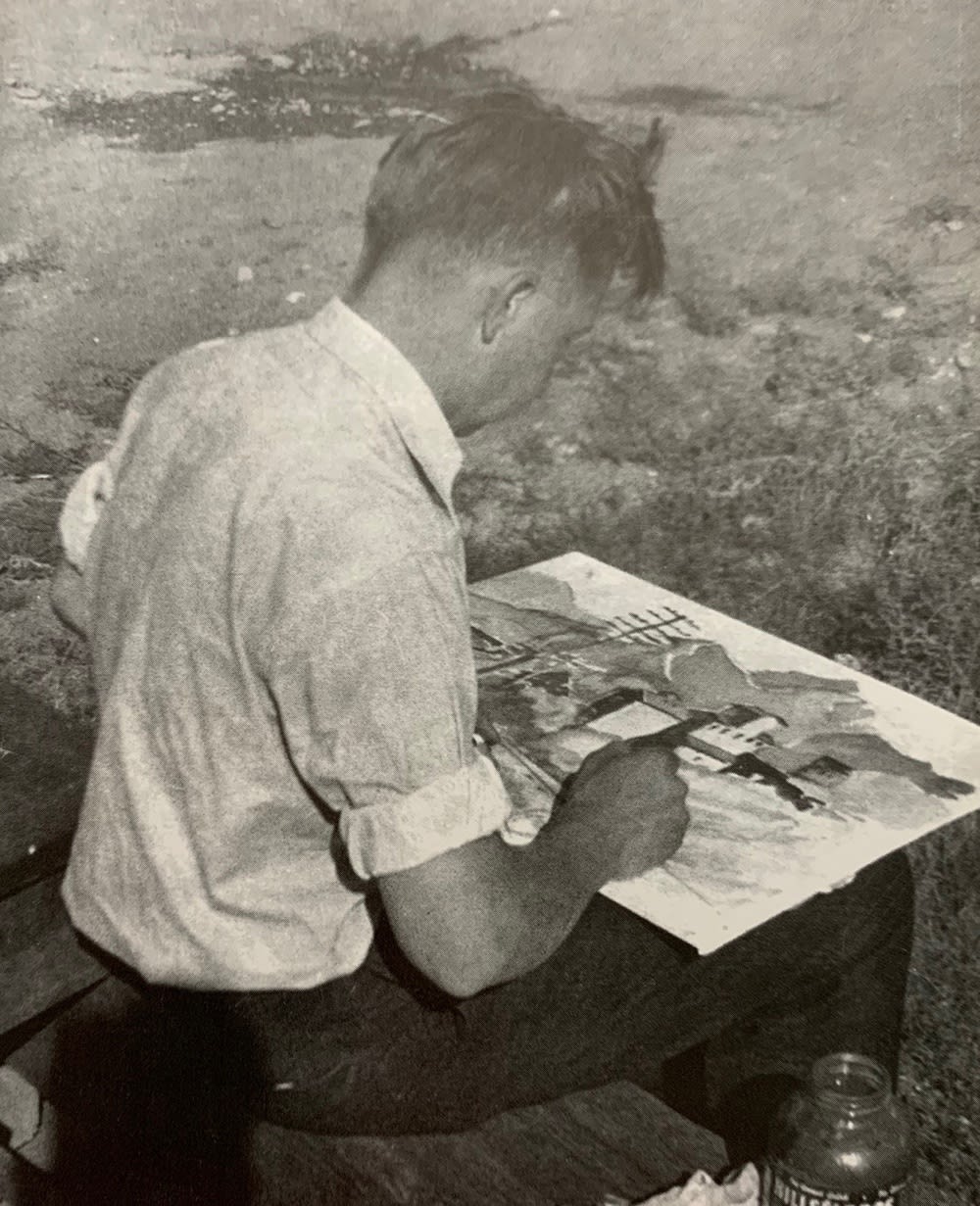

Autio painting a watercolor as a student at MSU, 1947

Rudy Autio was born in Butte, Montana, in 1926 to immigrant parents from Finland. At that time Butte was the largest city in the Mountain West, and Autio grew up in an essentially urban environment, with vast stretches of wilderness extending just beyond the city limits. He was raised in a neighborhood called Finntown, and spoke only Finnish until he went to primary school.

In the mid-1930s, as part of the Works Progress Administration, artists would occasionally come to Butte to teach community classes at night. This was Autio’s first real introduction to art-making. He took interest and had a knack for drawing. In high school he had teachers who helped him refine his skills with charcoal drawing, painting, silkscreening and other methods.

In 1944 Autio enlisted in the Navy. He attended Aviation Machinists School and was assigned to repair crews in Alameda, California, and Fallon, Nevada. After the war he returned to Butte, not yet 20 years old, unsure quite what to do with himself. One of his friends from high school was about to begin college at Montana State University in Bozeman, and needed a roommate. With the GI Bill, Autio could attend for free, so off he went, along with hundreds of other returning war vets.

Autio started off studying Architectural Engineering, but was soon lured to the Art Department. The program had good, experienced, demanding teachers, and Autio loved the breadth of assignments he was given. It was here that Autio was first exposed to ceramics by Frances Senska, a war veteran herself, who had recently joined the faculty and set up a basic pottery shop in the basement of Herrick Hall. Also at MSU, Autio met two classmates who would forever shape his life as a man and a maker. One was Peter Voulkos, who became a close, lifelong friend, and whose work would, within a decade, have a seismic impact on the burgeoning field of ceramic arts. The other was Lela Moniger, who Autio married in 1948 while the two were still undergraduates. Lela, too, would go on to have a very notable career as an innovative artist and art teacher. She and Autio remained married until his death in 2007.

The Archie Bray Foundation

In the summer of 1951, having finished his first year of graduate school at Washington State University, Autio returned to Montana and took a job working at The Western Clay Manufacturing Company. The job had been arranged by his friend Peter Voulkos, who joined Autio there along with another young artist, Kelly Wong. Western Clay was owned by Archie Bray, an art enthusiast and patron who had a notion to create a small center for the arts on the site of his brickyard.

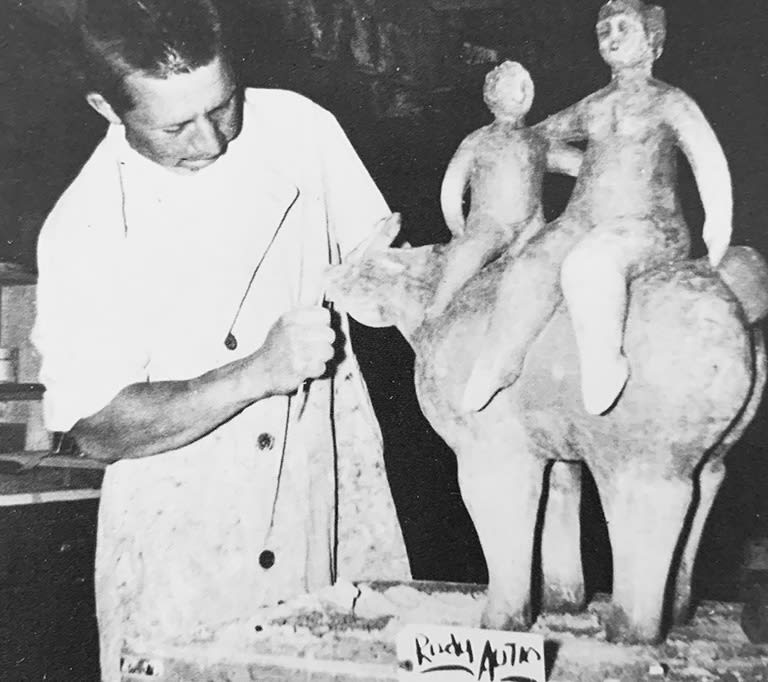

Autio working at the Archie Bray Foundation, 1951

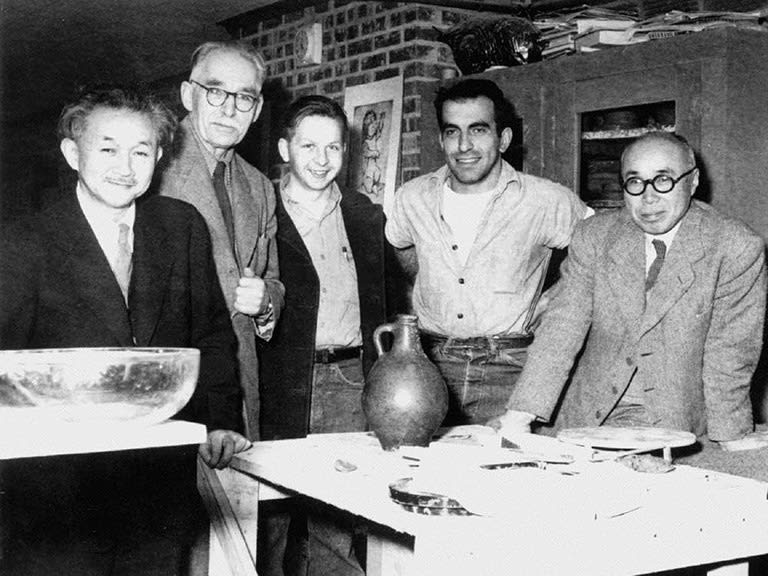

Autio with Bernard Leach, Soetsu Yanagi, Shōji Hamada and Peter Voulkos at the Archie Bray Foundation, 1952

Autio, Voulkos and Wong spent the summer working the brickyard, building a pottery, and, with what little spare time they had, making pots that they would fire in the large beehive brick kilns. In the fall, Autio and Voulkos returned to their respective graduate schools to finish their MFAs. In the summer of 1952 they came back to Helena, this time as Artists-in-Residence at the Archie Bray Foundation.

In the fall of 1952, the foundation’s trustees arranged for the Bray's first—and perhaps most famous—workshop, given by Bernard Leach, a master craftsman known as the “Father of British studio pottery”; Shōji Hamada, a major figure of the Japanese mingei folk-art movement; and Soetsu Yanagi, a visiting lecturer in Zen philosophy at Harvard University. The guests stayed in Helena for two weeks, demonstrating techniques for throwing and decorating pots, and talking about the ancient traditions they carried forward. The experience made Autio think differently about clay:

To see someone like Hamada...infuse it with a spirit that was as good as anything that could happen in painting or drawing and fine arts. I could see that this was a very important, almost spiritual kind of experience when they worked with clay. The economy of movement, everything that he did, the way he considered the piece before he painted on it. All of those things had a great impact on me.

The following year, 1953, was a momentous one for Autio and the foundation. Early in the winter Archie Bray was injured in the brickyard, developed pneumonia, and died. The future of the foundation was uncertain, but Archie Bray Jr., who inherited the brickyard, decided to keep it going in honor of his father. That year Autio took up one of his first major architectural projects—an 8-foot-wide circular medallion in ceramics, commissioned by the University of Montana for one of its buildings. He and Voulkos also submitted work to that year’s annual Wichita National Decorative Arts Ceramics Exhibition. Voulkos's hand-decorated tureen, which took first place in the functional ceramics category, and Autio's small sculpture "Bird and Egg" were both pictured in the July 1953 issue of Ceramics Monthly. Autio’s work was beginning to be recognized around the state and beyond.

Voulkos, whose reputation as a ceramist had begun to soar, left The Bray in 1954, having been hired to set up a new ceramics department at the Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles. Many other notable artists came through The Bray in those years, either as artists-in-residence or to conduct workshops: Rex Mason, Marguerite Wildenhain (a teacher of Frances Senska's), Tony Prieto, Carlton Ball and others. Autio stayed on a few more years, directing the residencies and working on more architectural installations. In late 1956, with two kids and another on the way, he went to California, looking for more stable and lucrative employment. When nothing panned out, he rejoined his family in Helena in the spring of 1957—just in time to learn that Carl McFarland, president of the University of Montana, was looking for someone to set up a ceramics department in Missoula.

University of Montana

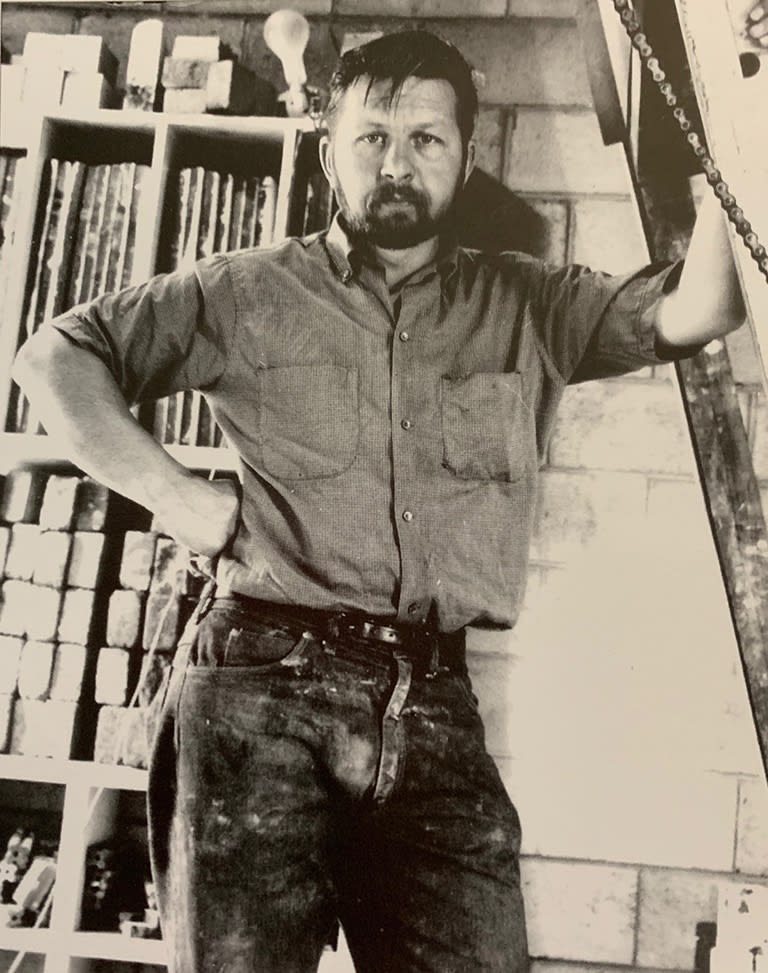

Autio in the University of Montana's Ceramics Department, 1958

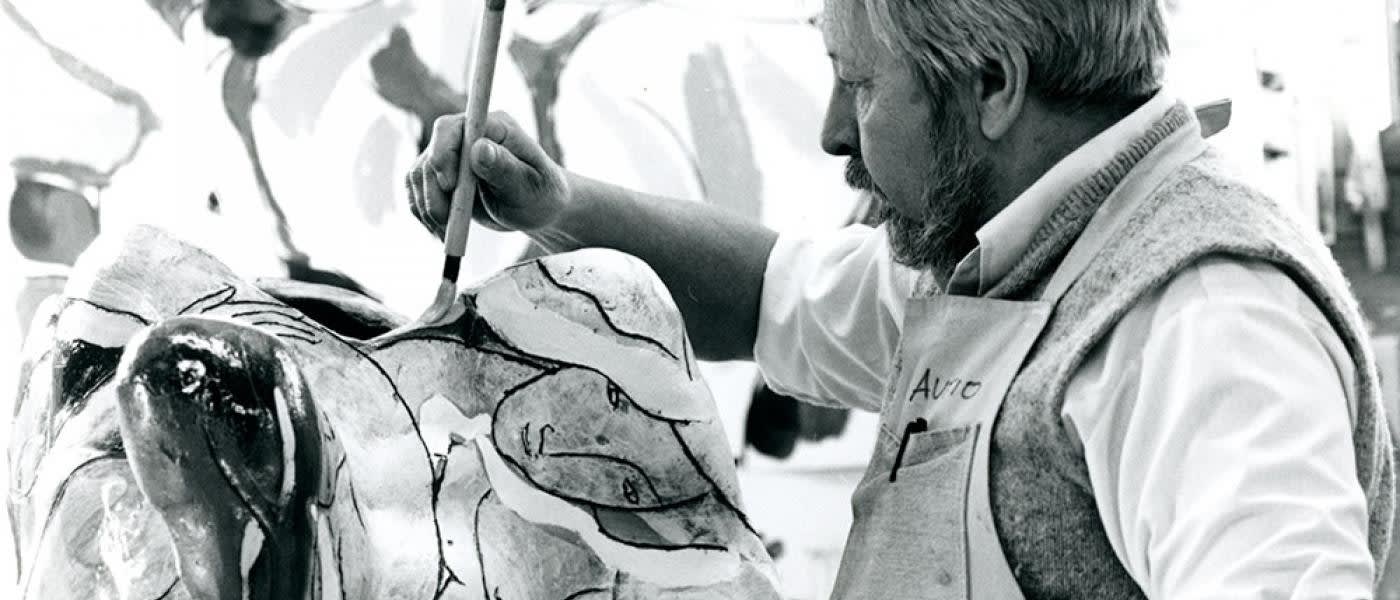

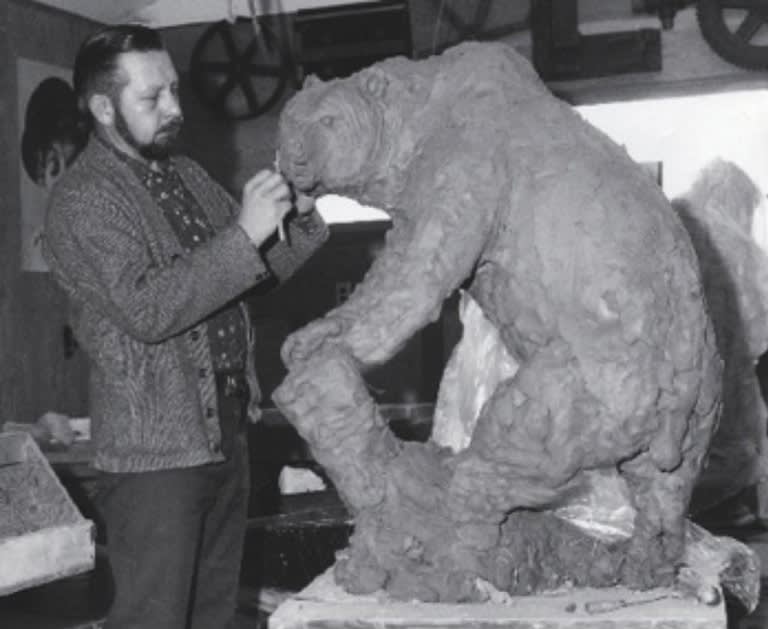

Autio working on a model of the Grizzly, 1968

Autio started with very little when he joined the staff of the Art Department at the University of Montana in 1957. "I had to scramble that first year trying to teach ceramics without a room and no clay, kilns that didn’t work and a class of interested adult students eagerly waiting for information." Piece by piece he put the program together. An old warming shed for a defunct skating rink and a WWII barracks would serve as his classroom and pottery. He built kick wheels, scavenged and repaired kilns, set up a glaze-mixing room. His colleagues in the Art Department—Walter Hook, James Dew and others—were supportive, and Autio was invigorated by the challenge of it all:

I began soon to get momentum. Brimming with ideas as my confidence grew, I'd run to the blackboard, sketch ideas quickly, and turn to new ideas and solutions all around me. I taught everyone who got in my way. Special students, grad students, everybody. It didn't make any difference. I was a college instructor now. I taught them everything I knew, and I never seemed to run out of projects for the students to do. My mind bubbled over.

At Autio's invitation, Peter Voulkos came to campus in the summer of 1958 as a visiting artist. The two worked on developing various clay bodies using locally dug clay and sand. They each made expressionistic pots and sculptures. Jim Melchert was one their students that summer. He impressed everybody with his creativity, intellect and curiosity—and would go on to have a monumental career as an artist and teacher.

Autio continued making large, site-specific architectural murals for various buildings across the region. Starting in the early 1960s he took an interest in bronze casting and experimented with it over the next several years. In 1968 he was commissioned by UM to create a life-sized bronze grizzly bear for the campus oval—a project that turned out to be much more onerous and time-consuming than he ever expected. Autio also experimented with sculpture in cement, steel and glass, and did relatively little work in clay—other than architectural projects—throughout the 1960s and early 1970s. But gradually he was drawn back to ceramics, largely through the encouragement of peers and ex-students who had gone on to have distinguished careers in the medium. David Dontinghy and Jim Stephenson were both students. The two would eventually reunite as instructors at Penn State, where they launched the national Supermud ceramic conferences that did so much to advance the legitimacy and popularity of the medium. Other students included Doug Baldwin, Fred Wollschlager, Jay Rummel, David Askevold, Martin Holt and Beth Lo. Lo would eventually step into the teaching position vacated by Autio when he retired from the University of Montana in 1985.

Public Projects

Around the world Autio is best known for his dynamic, colorful "ladies and horses" pots and plates, but Montanans are accustomed to seeing the artist’s architectural work around the state as well. Starting in the early 1950s, Autio contributed dozens of major artworks to public projects in Missoula, Great Falls, Butte, Helena, Bozeman, Anaconda, Cut Bank and elsewhere.

Autio working on Sermon on the Mount, later installed at the First Methodist Church in Great Falls, 1954

Montana Horses installed in the Performing Arts Building at the University of Montana

The first such project came to Autio soon after he started as a resident at the Archie Bray Foundation. He was commissioned to create a large circular medallion by the University of Montana. Autio conceived a design—a relief depicting a Native American writing on stretched animal skin—comprised of 24 sections. He created the mural first in plaster, then, using the techniques of old terra cotta craftsmen, made negative molds of each section from which he could cast the pieces in clay. The mural is approximately 8 feet in diameter and is installed on the south face of UM's Liberal Arts Building.

More projects would follow: a 10-foot by 30-foot carved-brick relief for the First United Methodist Church in Great Falls; a 12-foot by 4-foot glazed terra cotta relief for the Glacier County Library in Cutbank; a massive 16-foot by 18-foot carved brick mural for the Gold Hill Lutheran Church in Autio’s hometown of Butte. All this while Autio was still at The Bray, where he honed his technique for developing these complex, time-consuming projects.

After he joined the faculty at the University of Montana, Autio continued making public artworks—using clay as well as other mediums. He created the 8-foot high, 5000-pound bronze Grizzly for the campus. He created a 6.5-foot x 70-foot stoneware tile mural for the inside of Wells Fargo Bank in Helena. He created large freestanding abstract sculptures out of cement and steel for various public locations. He designed the stained glass windows for the chapel at Malmstrom Air Force Base in Great Falls. In the mid-1980s, Autio was again commissioned by the University of Montana—this time to create a large installation for its new Performing Arts Center. By then Autio had made several trips to Finland, teaching workshops at the Arabia Porcelain Factory in Helsinki, making work for exhibitions, and connecting with distant relatives. While in Helsinki, still mulling a design for the commission, he visited the Friends of Finnish Handicrafts Center and saw ryas—traditional woven tapestries—being made there. The idea occurred to him that a massive rya would be perfect to fill the space in the Performing Arts building. He spoke to the director of the Handicrafts Center about the possibility of making such a large piece, then came up with a design that met the approval of the University. Autio collaborated with Anneli Hartikainen, a master weaver in Helsinki, who spent the next 14 months creating the tapestry. The finished piece, titled Montana Horses, is 20-feet tall by 30-feet wide and weighs 440 pounds.

Legacy and Accolades

Gull Beach, 1999

Autio was a consummate maker—industrious and prolific. And the art world took notice. His work was featured in major group and solo exhibitions from the early 1960s until his death in 2007. His sculptures are included in the permanent collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Carnegie Museum, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian Institution, the American Craft Museum, museums in Finland, Sweden, Japan, and elsewhere.

Autio received a Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation award in Crafts in 1963, the American Ceramic Society Art Award in 1978, and a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts in 1981. Also in 1981 the State of Montana issued its first Governor’s Arts Awards, recognizing Autio as Outstanding Visual Artist. In 1978 Autio was invited to the American Craft Council’s College of Fellows, and in 1999 the ACC recognized him with the Gold Medal for Consummate Craftsmanship—the highest award given by the Council and among the most prestigious in the nation. In 2007 he received the Masters of the Medium award from the James Renwick Alliance. Autio was made an honorary member of the National Council on Education for the Ceramic Arts, and received an honorary Doctorate of Art from the Maryland Institute, College of Art in Baltimore.

Autio in his studio gallery, Missoula, 2007 (photo by Richard Notkin)

Autio has been called the "Matisse of ceramics," and indeed that influence is plainly seen in much of the artist's work. He allowed his life—his interests, his passions, his experiences—to inform and imbue his art-making. Matisse is there. Picasso is there. Peter Volkous and Frances Senska and Shōji Hamada are there. Lela Autio is there, always. Charlie Russel is there. Ancient Greece is there, and Montana. Finntown is there. And of course all these influences are drawn and held together by something that is purely, uniquely, Rudy Autio’s. His work is capacious. It has breadth and depth. It offers an abundance. At the same time, it is remarkably gentle, reserved, even humble—much like the artist himself. As Michael Rubin, in his forward to Rudy Autio Work 1983-1996, writes, "Rudy Autio's ceramic art possesses a quiet knowledge....the testing, observation, the decision to repeat or discard, shift the hue, thicken the line, each accumulate for a mature vision.... His quiet, soft spoken manner can be, like his art, illusive of his deeply held dedication." What is not illusive is the tremendous impact Autio had—and arguably continues to have—on the field of contemporary ceramic arts, as an artist, teacher and visionary.